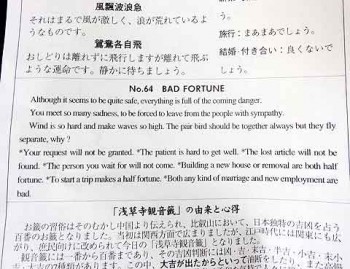

4-1/2 hours before Japan’s earthquake: it might have been my sister’s fault. Had she kept the slip of paper her bad fortune was printed on, as was her intention, blame certainly could have been laid. Instead, she folded the paper and impaled it on a tree branch in the ritual manner of rejecting bad fortunes. Surely by doing so she should have prevented the predictions she’d plucked only a few hours before the 9.0 devastation.

“BAD FORTUNE,” warned the English translation on her plucked paper. “Although it seems to be quite safe, everything is full of the coming danger.”

It was 10:15 a.m. on the first day of our family vacation in Japan. In Tokyo’s Asakusa district to visit the the Senso-ji Buddhist temple, all 16 of us were high on togetherness, anticipating the exotic experiences we’d carefully planned.

“You meet so many sadness, to be forced to leave from the people with sympathy.” Karen’s fortune continued. “Wind is so hard and make waves so high.”

“You should make an offering and get rid of it,” our Japanese guide explained. Karen folded the paper and stuck it to a branch.

4 hours before: As we left the temple compound, a mob of Japanese schoolgirls surrounded my blond, blue-eyed, buff nephew, taking turns snapping photos of themselves with him. Nick felt like a celebrity—and acted like one. We were all certain the photo-frenzy would be the highlight of our day.

3 hours before: Our next stop was the 790-foot-tall Sunshine-60, a skyscraping tower capped by an observatory on its 60th floor. One of the fastest elevators in the world blasted us to the top, from which we looked down on the dense city. Strangely, we watched seal-training on a rooftop below.

The earthquake, now less than three hours in the future, would have swayed the observatory to a sickening and terrifying extent. The speedy elevators would have been shut down. Alone but for a few young staff members, we’d have been stuck in the stratosphere for the huge aftershock 30 minutes later, petrified.

1-1/2 hours before: After lunch we visited a house in a residential district for a traditional tea ceremony. First, we were each to be dressed in kimonos—a long, arduous process, we learned, with their many layers, and the tugging and tying of the obi, the wide, extravagant sash tied elaborately in back.

9.0 Earthquake

Earthquake! I was half dressed when the rumbling began. Lamps, scrolls, and empty hangers rattled while the house seemed to be surfing mad waves. At first, we hustled into doorways—many of us had been trained as California school children. Moments later, the staff ushered us under their two large tables. The house also functioned as a cooking school, so the two tables were big enough to shelter all 16 of us.

The staff threw open the doors and windows—as they are trained, I later learned, to enable escape should walls shift and doors jam. Meanwhile, the bumps and jerky rolls continued. For two full, long minutes, we rode the rocking floor bent double under the tables, some of us already bound tightly in traditional Japanese dress.

I’m no stranger to earthquakes. I was in “the big one” in Los Angeles in 1971, and many smaller ones. Most of them last a good 20 seconds or so which, when you’re in one, feels like a long time. This one just wouldn’t quit. Crouched and crowded with my family, I wondered how many floors the tables would support. And how many stories high was the building we were in, anyway? Should we run outside? Why hadn’t I noticed more about the neighborhood?

Some of the staff were kneeling, hands together, praying. One of our children wailed. There was nervous laughter and inappropriate joking. There were tea cups falling in their cabinets and weird, whistling sounds. We all had the same thoughts: how long would this go on? And: this is our whole family. My parents, their four children, some spouses, and five of their seven grandchildren.

4 minutes after: When we emerged, we looked around dazed and confused. There wasn’t much evidence of damage in the house, but cell phone service was down. Without radio, television, or phone, we didn’t know the severity of the quake. The staff looked shaken, but quickly got back to their duties. I was shoed back into the dressing room for obi-tying along with my niece, who was also half-dressed, and my sister, who was photographing. All of us nervously watched the lamp, hangers, and scroll, and noticed that they never totally stopped swaying.

30 minutes after: The first huge aftershock came soon after the earthquake—about 10 minutes after we’d resumed our activities. We dove under the tables again, those of us who appeared calm soothing the ones who let their fear show. We were all scared, floundering, and aware of how helpless we felt.

One of my sisters got news on her Blackberry. The quake was first measured at 8.8—huge. There were no immediate reports of damage. We studied the staff members for signs of fear or distress. To us, they appeared a little distracted, but resolute, ready to push on with their characteristic dignity. A little familiar with the national ethos, this did not necessarily fill me with confidence that all was well.

We soldiered on through kimono-dressing and a somber tea ceremony, only half interested, whispering worries and nervously joking. The Japanese showed no emotion. They maintained perfect grace and extended courteous hospitality. At 5:00, we left the house, only then looking up to see what had been above us.

1 hour and 15 minutes after: By then, traffic was at a standstill. The sidewalks were surging with office workers, many wearing hardhats. Our vehicle had satellite TV tuned to Japanese news. We got our first horrendous images of the raging fires and tsunami damage. On every station, maps of Japan blinked with garishly-colored tsunami warnings. We learned that all trains had stopped running. With traffic jammed, even buses and taxis would not be able to get office workers home, many of whom live an hour or more commute outside of Tokyo. They’d be walking all night.

4 hours and 15 minutes after: The five- or six-mile drive to our hotel, the Peninsula, took three tense hours. The lobby was full of stranded workers. A scribbled signboard promised the hotel would provide food and drinks to all. We worried about our two magnificent guides, who would be as stuck as everyone else in the city. We decided to double up: three sisters and one husband sharing one room, freeing one of our eight rooms for our guides. It took much cajoling before they gratefully accepted our offer.

Our dinner plans had been scrapped and, with gas stoves shut down, the hotel’s kitchens were only semi-functional. My nephew set out to find groceries, but returned to report that all shelves were bare. We weren’t really hungry anyway.

5 hours after: We hunkered together, reluctant to separate from other family members, opened wine, and nibbled mini-bar nuts in front of the news. Hyper-aware of our rooms being on the ninth and 18th floors of a skyscraper, we considered choosing an emergency meeting place. Everything seemed uncertain, though. What would the world look like in an emergency? What’s a good meeting place in a landscape of skyscrapers?

Aftershocks rocked the hotel every ten or fifteen minutes. The highways below were parking lots. I came across a video showing Tokyo’s skyscrapers swaying after the earthquake. It wasn’t until we turned off the television and got into bed that we heard the eerie creaking of the building. Only those who popped pills got any sleep that night.

The Japanese are often characterized as stoic. This trait has been pointed out relentlessly over the following days, and for good reason. Where possible, people carried on as usual. Little emotion was shown. Life goes on, even for survivors in the most devastated areas.

For us, too. We cried for the country we cared enough about to visit. We are heartbroken for the Japanese, for those we know and those we don’t know but know about. Yet, there we were, wondering: what now? What should we do?

1 day after: Glued to the TV, thankful for Blackberry news when away from it, we debated our course of action over and over. Should we leave? Are there flights out? Is it safe to stay? Insensitive? What reports can we trust, anyway? Are the Japanese being forthright? Is CNN dramatizing? BBC overly cautious?

With major changes to our itinerary, we stayed—one day at a time. We were constantly aware of the dichotomy between the massive devastation and our frivolous holiday. It felt strange to continue. Queasy. Callous and selfish.

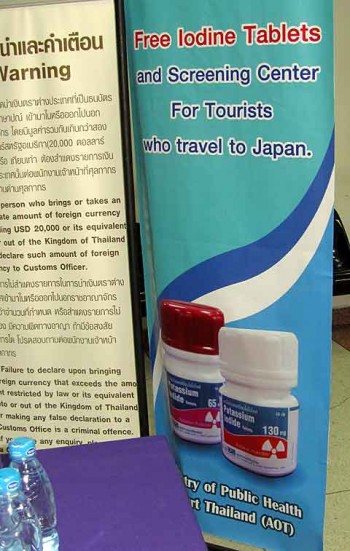

Each day, we all received concerned but hysterical emails begging us to leave. Fears of a nuclear meltdown and radiation leakage brought new worries. Not for us so much as for our five teenagers. We moved south and west, as planned, first to Hakone, then to Kyoto. Our flights at week’s end were to be out of Tokyo. Would the city be safe then? What if we flew to Tokyo, then couldn’t get out?

3 days after: Rolling blackouts were announced, to save power. We diligently turned off unnecessary lights in our luxurious rooms, irony not escaping us. The papers criticized the power-hogging vending machines that my family had been so entranced with. Each machine serves both hot and cold beverages. You can have a bottle of hot green tea or cold maple-syrup pancake drink on any street corner.

7 days after: We had flights from Osaka to Tokyo, from which we’d all be flying onwards: some were going home, some to Beijing, one to Vietnam, and I was going to Hong Kong. Reactors at Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant seemed to be exploding daily. With the situation so unstable, we agonized over returning to Tokyo with our children. In the end we did though, and were treated to one last, large aftershock in the airport, shortly before our flights.

15 days after: Flying through Thailand, I come face to face with a health screening desk for passengers flying to Japan. Free iodine tablets are on offer. I wonder if I should partake. I’m flying through Tokyo again on March 31 and radiation levels are increasing. Even today, just writing this report feels frivolous in the face of headlines.

Our trip was a celebration of my father’s 80th birthday. He and my mother chose Japan because they love the country’s people and its culture. In a world of conflict, I’m sure they also considered it safe for the family. The week became one of conflict anyway: worry and fear and festivity and pleasure. And though we’re all still riveted by the news out of Tokyo, for us it’s over. Not so for our new and old friends in Japan.

4/25/11 edit: While we were blithely dressing in kimonos, the tsunami was rolling in (unbeknownst to us, of course). See this horrifying video to its end.

* * *

Read about Japan’s complicated shoe rules.

Read about a Japanese kaiseki dinner.

5 Comments

[…] I never saw the same serving piece more than once. And all of this was managed just days after the earthquake and tsunami, under the threat of nuclear meltdown, between scheduled rolling blackouts. Praise and […]

[…] In Japan, people do not eat or drink on the street. In China, street food is a joy of life. (On the other hand, Japanese people do not hawk up and spit globules in public.) For portability, many Chinese snacks are sold on sticks, added eco-benefits unintended. Skewered frozen fruit embedded in ice makes a festive and refreshing snack or dessert. Strawberry sticks are coated in sticky caramel that floats across the face in long invisible threads with every bite, then hardens in the teeth long after the juicy fruit is gone. […]

Fabulous reporting. +1.

Great report. You write so calmly about our experience. We spent a long time under the table, it was very frightening and tense because of the violence of the shaking and the length of time.

The Japanese people behaved kindly to us, and to each other, and always in an ethical manner. You are right, our hearts break for them.

Thanks for the blog, #1. Got plenty of news (facts) elsewhere. Reading your blog was an insight into what was going on, thoughts and actions, from a personal level. What an experience!! YELU