“The mere mention of Colon sends shivers down the spines of travelers and Panamanians…”

After the brutal armed robbery of 18 tourists in Nassau three weeks ago, and our naive trek through the world’s most dangerous city, Port Moresby, Bob and I have had muggers on our minds. For years, we’ve studied non-violent pickpockets and con artists, and advised travelers how to avoid becoming their victims.

Muggers, though, are a different breed, defined—by us—as those who use violence or the threat of violence in the course of robbery. Often drug-addicted and desperate, their behavior is unpredictable and not easily avoidable.

Ask your hotel staff and local hosts where it’s safe to walk, we say. Carry “give-up” money. Be compliant, give them your stuff. It’s impossible to know what these desperadoes are capable of. Beyond that, we didn’t have much to say about muggers.

That changed a few days ago, when Bob created an opportunity. We were visiting Panama’s second largest city, feared by the capital’s police as well as savvy expats.

Having heard how dangerous Colon is, I left my camera in the hotel and walked the streets with empty pockets. Bob brought a video camera and a collapsing monopod. Immediately, we were approached by many aggressive men who wanted to show us the sites. We waved them away until we met Gustavo and Carlos, gentle, low-key men. Both scramble for whatever odd jobs they can find: construction, painting, roof repair, escorting visitors to the Gatun Locks.

Gustavo, 38, spoke decent English and was more than pleased to fulfill Bob’s challenge: take us to the most dangerous streets, and introduce us to some banditos. “Nobody wants to see my city,” Gustavo sighed later. Everybody just wants to go to the locks, or to the mall to buy t-shirts.”

I admit to starting this adventure a little uneasily. We don’t speak Spanish, for one thing. And I remembered the scary vulnerability we experienced when two knife-wielding thieves in Peru took us in a taxi to a “quiet place” of their choosing. And the way we were followed and scrutinized in Valparaiso, Chile, when we were pretty sure we saw the flash of a blade. And the gangsters we met in Panama City. Not to mention the emotional aftermath of Nassau’s 18 armed robbery victims.

Had I read what one Colon tourism site had to say, I probably wouldn’t have gone at all:

“Though exaggerated, Colon’s reputation throughout the rest of the country for violent crime is not undeserved, and if you come here you should exercise extreme caution—mugging, even on the main streets in broad daylight, is common. Don’t carry anything you can’t afford to lose, try and stay in sight of the police on the main streets, and consider renting a taxi to take you around, both as a guide and for protection.”

That from a site promoting the city!

We trusted Gustavo instantly, although the city looked, uh, “dicey,” to say the least. He led and Carlos guarded from behind, both pushing bicycles. “Robbers will not be difficult to find,” Gustavo admitted, “They are everywhere. They live on my street.”

Colon’s gorgeous colonial architecture glowed under a hot sun, its faded Caribbean colors covered with graffiti. The place is crumbling. Potholed streets run with overflowing sewer water and heaps of trash. Cracked pavements and treacherous gutters vie for attention, with two-by-fours stretched across particularly rough stretches—inner-city balance beams.

“Hold this,” Bob said, passing me his monopod while he shot a little video. Not “Honey, you better stay home,” as many a husband might say. I gripped the photographic tool like a weapon, and later realized that it must have looked like one. Not a very nice visitor who tours a city wielding a police baton. Better leave her alone!

Gustavo pointed out the sights as we walked; sort of a walking tour of gangland central. Here’s a building used in a James Bond film shot last year. The men over there, they’re too dangerous. That street is very bad; we won’t walk there. This street is the home of three pandillas [gangs]. Colon has at least 50.

I looked at the blood newly splattered on my pants and shivered. Right… the butcher chopping chicken in the crowded market we passed through.

“Stay close,” Gustavo said. “No one will bother you when you’re with me. I know everyone.” Indeed, men, women, and children greeted him at every step, but he politely deflected them and focused on us.

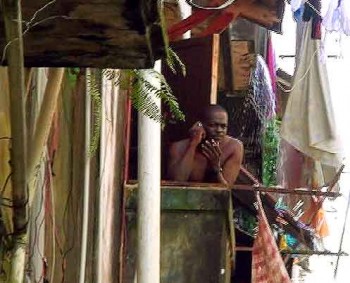

“That guy’s a robber,” Gustavo pointed, and called him over. Explaining our mission, he spoke with such authority the thief had no choice but to comply. Bob tossed the camera to me as we stepped into a filthy alley. It reeked of pee. Above, a man watched us from a balcony. Water gushed from another balcony, higher up.

How I mug

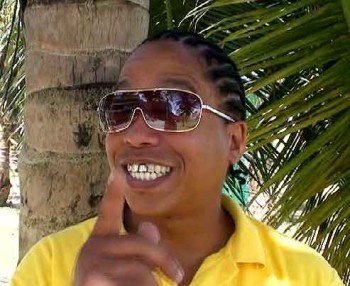

It’s hard to believe that Dajanel [Die-a-NEL) is a mugger. His sweet face, slight build, and compliant behavior belied his vocation. He robs with a gun. He doesn’t fire the gun, he told us—small comfort to his victims. Or huge comfort to his victims, I guess.

Dajanel likes to work as part of a structured threesome. One man grabs and holds the victim, one watches for police, one lifts the wallet. He scopes his marks as they come out of hotels, or as they buy drugs or girls. He looks for thick wallets.

Before a theft, Dajanel fortifies his nerves with drugs. We couldn’t ferret out his drug of choice but, whatever it is, it grows his strength and power. When he seizes a wallet, he goes straight for the cash and dumps the rest. ASAP. He doesn’t use credit cards, doesn’t sell them on. Holding them is evidence against him, and commands a higher sentence if he’s convicted of a crime.

Dajanel’s only 26, but he’s already spent three years in jail. As proof of his toughness, he pulled down the neck of his t-shirt to show off a thick scar on his shoulder—a deep knife wound that took three years to heal. He reminded me of Petter in Lima, who showed off his many scars, and Angel, in Panama City, whose little bullet wound was a badge of honor. Dajanel raised his knee to display the entry point of a police bullet, and another in his foot.

Gustavo translated like a pro throughout the interview, while Carlos watched my back, his bike arranged like a police barrier at the alley entrance. I was hyper-aware of the million-dollar camera in my flimsy fingers—it might as well have been worth that much. A steady stream of passers-by stopped to watch—to see what was in it for them? Carlos moved them on.

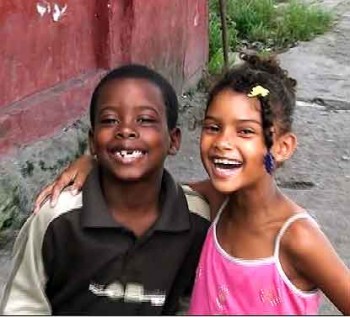

We walked on 6th Street after we let Dajanel go, where Gustavo lives. He brought us into his tiny, dark apartment, to meet his wife and four small girls. He has three older children elsewhere, he told us, though he’s only 38. Music was blasting in his apartment, as if he were force-feeding rhythm to his kids. Bob delighted them with a few magic tricks.

Exiting the long, dark hall to Gustavo’s interior home, we met Jaer, a 34-year-old robber.

Unlike Dajanel, Jaer prefers to work alone. That way, he doesn’t have to share money or worry about a partner who, if caught, might squeal. Unlike Dajanel he doesn’t use a gun; he steals anywhere, at any hour, but prefers early morning, because there are fewer cops around. He does not profile his marks. His weapon is speed, as in quickness, and brute force, as in a chokehold from behind. He oozes confidence and control. He doesn’t use drugs.

“Show me,” Bob said, no caution left to throw to the wind. “But not here. In private.” Yeah, where no one will see the mugger with his two rubes. Bob followed him down an alley only four feet wide to an interior courtyard the size of a tollbooth. “Now, show me,” he said.

Jaer backed up to the extent he could. So did I, attempting to get the whole scene on video, but even wide angle wasn’t wide enough in this close space. Jaer lent Bob his wallet, and stepped back over puddles of mud and water for a two-step running start.

Pow! The wallet was gone, and Jaer’d have been a block away had there been any place to run. He smiled with pride as a miniature gang of children passed through the shady space.

“Wow,” Bob said, “that’s the fastest steal I’ve ever seen! Again.” This time, Jaer surprised Bob with a chokehold, lifting the wallet in a one-handed plunge. The demo proved him experienced and capable.

“Now you,” Jaer requested, replacing his wallet in his pocket. After a suitable pause, Bob stealthily swiped it.

“I didn’t feel it,” Jaer said. “I’m impressed. Your way is much better. But speed is vital. I don’t think you could run away fast enough.”

He left Bob with a final word: “I’ll be talking about you tonight…”

* * *

What the U.S. State Department says about Colon:

“The entire city of Colon is a high crime area; travelers should use extreme caution when in Colon.”

—Panama Country Specific Information, 8/22/14, U.S. State Department