Our Data, Our Selves

They know who you are. They know what you buy, where you live, where you work, where you go in between. They know your most intimate secrets, not because you told anyone; they simply put the clues together and joined seemingly unrelated tidbits. Your shopping history, your online searches, words used in your email, the cell phone towers your phone used, even how fast or slowly you type. Combined, it all points to you. You leave data dribbles like greasy fingerprints to be dusted, collected, identified, and assembled.

By now we’re all used to being tracked and spied upon. We pretty much accept it, most of us. We know our web-browsers act as spies and report our every move. Our credit cards and loyalty cards provide a treasure trove to someone (but who?), and our cell phones even more. We’re spied upon even with the cameras and microphones built into our own computers and cell phones. What can we do but shrug our shoulders and give up?

We’re vigilant about not clicking on spammers’ links, we’ve learned to look for “https” URLs when we make online payments, even to recognize spoof emails. But enough is enough, right? We have to live life! Today’s technology is as vital as food and water and we have to use it. Who can spend time worrying about all this info-gathering, especially since it’s invisible, and does not present an inconvenience. Forget it. That’s life. Move on…

Or…?

Trade-offs

We constantly and willingly give up our data for something in return. And it seems like a fair exchange: handing over data is painless; the benefit is all ours! We get free stuff, convenience, points, discounts, rewards, elite status, the privilege of using a “free” app… [Warning: rant coming…

WhatsApp is my pet peeve. Many, many of my friends and colleagues, even those in the security business, use it. And what’s the first thing the app does after you download it? “WhatsApp would like to access your contacts.” “OK,” you say and—whoops!—there they go, all your contacts, including my info if I’m in your address book (and I’m not even a user!), against my will, handed over so WhatsApp and facebook can “share information with third-party providers,” in other words, so they can sell my personal info. Thanks, friends. Yet, prominently, ironically, WhatsApp proclaims on its site “Privacy and Security is in our DNA.” Okay, its messages are encrypted, but what’s private or secure (or honest) about sucking up all the contacts of a naive user? True, WhatsApp is not the only app that commits this surreptitious theft of information. Uber is another. But, I digress. …Whew. Okay, end of tirade.]

Where was I? Trade-offs. Security is a trade-off which costs us in convenience, simplicity, expense, dignity, time, and much more. Wouldn’t it be swell if we didn’t need passwords, locks, or TSA? But we do need these, obviously. Luckily, the average person can deal with the minimum required amount of security.

Privacy is another matter though. We can shut our curtains but… do you have tape over your webcam? Put your birthday on facebook? Unknowingly hand over all your contacts’ info to What’sApp or some other software company? Use a credit card, loyalty card, agree to “our terms and conditions”? Yeah, privacy is pretty hopeless nowadays. If you browse the internet or use a cell phone, you’re being tracked. Not only tracked, but micro-tracked. Data about you is collected at every turn, codified, traded, bought, sold, and used to build a scarily detailed dossier—which is also bought and sold. It’s your data shadow; it sticks to you and grows as the minutes pass, like the setting sun’s lengthening silhouette attached to your feet.

In fact, data you enter on some web forms, for example Quicken Loans’ Mortgage Calculator, is sucked up even before you give it permission by clicking “submit.”

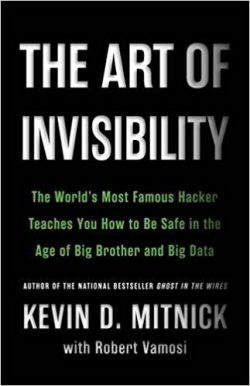

The Art of Invisibility, by Kevin Mitnick

To avoid being tracked, to stay under the radar and off the grid, to be invisible, is a huge trade-off. A Sisyphean task. Kevin Mitnick lays it out in his book, The Art of Invisibility, step by step. And he should know, having evaded the FBI for two and a half years before he was arrested and imprisoned for five years. Remember “Free Kevin”? I highly recommend Kevin’s entertaining and page-turner previous book, Ghost in the Wires: My Adventures as the World’s Most Wanted Hacker.

Entertaining, The Art of Invisibility is not. Page-turner…uh-uh. But it is fascinating, and after a good primer on the basics, goes into technical detail that might be more interesting than useful for many of us ordinary people. For every scary spy technique revealed, Mitnick tells us how to avoid that particular trap. They’re not easy to thwart—short of living in a cave secluded and self-sufficient, it’s a lot of work. As in, huge trade-off. And Mitnick tells us repeatedly: we will make a mistake. We will trip ourselves up. That’s how hackers and leakers are discovered. They make some tiny mistake that allows them to be traced and their identities revealed. But most of us don’t really want or need invisibility. We just want to avoid the obvious pitfalls and take, at least, the easy precautions.

Mitnick tells us there’s much we can do easily, and tests we can run to see just how vulnerable we are online. We should do as much as our tolerance allows, up to our own personal trade-off limit. You lock your car, right? Do you use a LoJack? You lock your home. Do you have a security system? Do you use it? Do you have iron bars on your windows? We’ll each go to a certain level, then hit our quitting point.

Simple, important steps include turning off location-sharing, blocking pop-up windows, deleting cookies, killing super-cookies, using end-to-end encrypted messaging, and many, many more.

But to truly reach online invisibility, Mitnick addresses three large categories: hide your real IP address; shield your hardware and software; and defend your anonymity. The hoops one must clamber through for each of these are many and challenging.

You can hide but you’ll still be seen

Offline is another matter. How many times per day is your photo captured by surveillance video or someone’s ordinary camera? What might they do with it? Are people flying drones over your house? Retailers can now capture the identity of your cell phone when you enter their store, and look up all kinds of details about you. So can law enforcement, in large crowds of protestors, for example.

Facial recognition software is in use in some places, namely churches, to log your attendance, and not necessarily with your knowledge or permission. (Fix: wearing special, light-emitting glasses.)

You’re tracked in multiple ways and recognized using almost every form of transportation (bus, train, subway, taxi, your own car). Uber maintains your ride history; and that’s nothing compared to what Tesla knows about its car owners. And get this: if you take a subway train, the accelerometer log on your own cell phone can be matched to the subway line you took and exactly where you boarded and debarked. Is that creepy, or what? (Fix: drop out of life entirely?)

Have a voice activated TV? It’s listening for your command; what else does it hear, and where does the speech it records go for recognition? Use Siri, Alexa, Google Assistant, or one of those voice-recognizing gizmos? They’re always on and listening; how secure are they, and who’s eavesdropping? Where does the recording go for artificial intelligence interpretation and how long is it stored?

What do you have connected to your home network? Lighting, doorbell, thermostat, baby monitor, pool control, security system, door lock, webcam, refrigerator? The Internet-of-Things (IoT) is most troublesome, because most of these peripherals you control with your phone or tablet are not built for security and are not patched or updated. A hacker can use these convenient connected systems to gain access to your entire home network. (Fix: live in a cave?)

“To master the art of invisibility, you have to prevent yourself from doing private things in public.”

Need to conduct personal business while at work? If you want it to be private, don’t use company computers, printers, or company issued cell phones. Use your own, personal device, and use your own personal cellular data network, not the company wifi. Actually, don’t use any other wifi, devices, or printers, including the library’s or the copy shop’s. They all save logs and PDFs of documents you print that you can’t delete. Your data crumbs are dribbled everywhere by default; actively preventing the leakage is not easy.

(A top secret foreign military unit recently hired Bob and me for training. But because of the insecurity of communications, and because Bob and I, mere civilians, did not have access to a “cone of silence,” the group flew us overseas without even telling us about our assignment. That’s military-grade security.)

I got a special kick out of the beginning of Chapter Fourteen. Mitnick describes a harrowing incident in which he was detained for hours by customs agents upon flying into Atlanta from Bogatá. Bob and I had also flown into Atlanta at the same time, and were to speak at the same security conference, the American Society for Industrial Security (ASIS). We were waiting for Mitnick at the airport… and waiting, and waiting. We finally left without him, and learned late that night what had happened to him, which you’ll have to read the book to find out. He was cool but shaken, if one can be both of those at once, and angry because he was unable to prepare properly for the panel he’d be moderating in the morning.

Mitnick lays out the pitfalls and tricks of returning to the U.S. from abroad, and how to keep your data out of the hands of curious Customs and Immigration officials. He explains in great detail how to use a Tor browser, a VPN, and Bitcoin to set up anonymous browsing; oh, and first turn off your home network, use a separate computer (which you purchased anonymously with cash), change your MAC address, use a personal hotspot on a burner phone (purchased anonymously), stay on the move, and remember not to check Facebook or your personal email. I skipped some steps, but you get the idea.

Know the difference between the Surface Web, the Deep Web, and the Dark Web? Mitnick explains all that, and why a law-abiding citizen might have a legitimate need to browse anonymously. If you really want to do it, all the steps are detailed. It’s a lot of work. And, as Mitnick emphasizes, a nanosecond of lapse will blow it all completely.

One thing Mitnick does not address in The Art of Invisibility is healthcare. I wonder how he would get medical treatment if he were trying for invisibility today? How did he do it when he was on the lam in the 90s (though things were much different way back then)?

I have to ask him that. If I can find him…