Bob Arno writes about his brother. Bambi interrupts.

Over the years I have written about my mentors, my old friends who have had a significant impact on my career, as well as a few obituaries — friends who were taken from us way too early. Writing about mentors is not hard, just go back in time and analyze why they were unique and how they extended themselves and helped a young inexperienced entertainer.

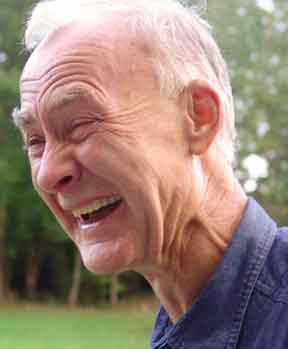

But today I have a far more personal challenge, in the midst of my sorrow for the loss of my own brother. He passed away about ten days ago, at age seventy. That’s far too early for a Swedish man who lived healthy, never excessive, and always in great trim shape.

Bambi: It was only two summers ago that he lifted tall Frida from the ground when she hurt her ankle on a trampoline in Arizona, and carried her like a baby a long distance to a sofa. He carried her as if she weighed nothing. In retrospect, we know that Claes was already ill, though none of us knew it. But he was still strong as an ox!

How does one explain the random selection of cancer victims? In my work I am obsessed with pattern recognition and the logic of why some people become victims (to criminals)—it’s all very neat and clear when looking at the bigger picture. But cancer can strike anyone, young or old, with little warning, as was the case with my brother. A little over a year ago he noticed he couldn’t quite swallow food as easily as before. He suspected some sort a throat infection. In September 2013 the tests came in: advanced esophageal cancer, located at the bottom of the esophagus, as well as smaller tumors in the stomach. No option to operate, only chemo therapy remained.

The doctors gave him a year, at best, and that is exactly what he got. In this year he never gave up, never resigned, but knew deep down that it was probably hopeless. He prepared as most cancer patients do for the inevitable. The legal documents, the transfer of properties, the farewell parties with his closest friends. Nobody around him suspected the rapid deterioration. Yes, his weight became an obvious red flag, but he did not look gaunt, and his face had the same round, filled-out cheeks as before. When he was in a good mood, nobody could possibly suspect that we all counted days and weeks.

My brother, Claes, lived in Sweden, where end-of-life health care is exemplary and caring. Every evening a nurse came by and hooked Claes to a drip tube, connected to a port in his upper chest close to his neck. During the night he would then receive about a liter of a milky nutritious fluid, while sleeping. Every morning the nurse returned and disconnected the tube. No, it was not good “quality of life,” since he could barely eat anything at all for close to a year. Always nauseous, and during the last six months of his life steadily more in pain, as the tumors grew and pressed against spine and sensitive nerve centers. Strong doses of morphine only sometimes helped.

So why did he maintain the illusion that maybe there was still hope for a new miracle drug? Stronger men at age 69-71 might have said “I had a good life, enough is enough, let’s not pretend anymore.” But Claes enjoyed every minute he had on the telephone with his friends, with me and my wife, and simply living another day. For 365 days when I couldn’t be with Claes, I called him daily for about an hour. We stayed with him whenever we could and behaved like we always did. Sat around the dining table and joked around, talked over current events, old anecdotes, and memories. There were lots of those and lots of laughter.

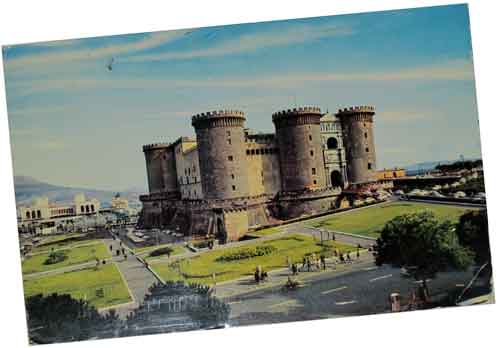

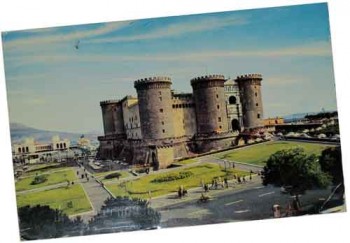

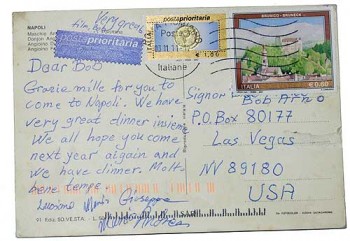

Bambi: Like that utterly believable postcard Claes sent us from Naples, pretending to be a gang of thieves thanking us for visiting Naples, and complimenting the film National Geographic made about us and them. It was brilliant, the way he mixed a little Italian in with poor English. Did Claes, with his love of all things Italian, and his reverence for the ultimate practical joke, travel to Naples just to send that postcard? It would be just like him…

But I never brought up the obvious: what do we do for Claes’s funeral, who should attend, how should we deal with this or with that? We both pushed aside the inevitable, the closure of it all. But he was not living in a dream world. He knew full well that some things just had to be done, despite the great expense in terms of his energy.

Sweden does not seem to have an end-of-life option for the patient, as is the case in the Netherlands and Switzerland. But there does not seem to be a heated dialog, either, like in the United Kingdom, about patients’ right to request a doctor’s help to terminate life. Having watched my brother suffer for a year I must ask myself why there are no choices. I’m not going to list all the horrible and painful moments my brother experienced in front of my very eyes. In retrospect, when everything is said and done, I think he still would have preferred to live just the number of days he squeezed out of his treatment and the help from the Swedish medical support system. But I would have chosen a different tack, which only means that people have different preferences and there should be an option for ALL. Not forced medical support (for whatever reason).

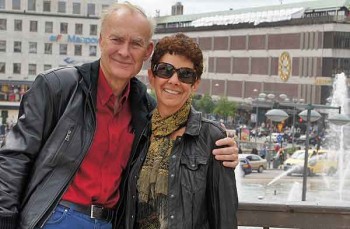

My relationship with my brother was unique. During the early years of my career he helped extensively with the management of promotional material back in Sweden when I was traveling around the world. But my work in the sixties was mainly outside of Sweden with few visits to my home country and so we were not as regular or intimate as in later years. Long distance phone calls in those days were costly affairs, only to be used for urgent matters. It was not until the early eighties, thirty five years ago, that I re-cemented my close friendship with my brother and we started to visit each other’s homes. Eventually this grew to extended stays on two continents, permanent possession of each other’s house keys, and “my house is your house.” We regularly visited one another for months on end.

Bambi: When in the U.S., Claes often referred to himself as an “Okie” or a country bumpkin when he felt unfamiliar with an American tradition. Like the time he drove alone to a plant nursery and his car was rushed by a gang of shouting Mexicans. Cold sweat, pounding heart, knuckles white on the steering wheel, Claes inched forward, terrified. Oh, did we ever laugh about that experience! Just a word of the story could forever after bring any of us to gales of laughter.

The friendship was equally warm between Claes and my wife. They were like brother and sister. We were a unique trio with shared interests and missed each other very much when apart. I would assume that only married couples or siblings can have the kind of close and warm relationship that years of sharing fosters. It was the humor, the jokes, the ribbing, the advice, the practical jokes, the insults, and the support, that was unique and is now missed.

Bambi: How could I not tease him about the creative way he shelved his books?

There wasn’t a dinner or a telephone chat (thank you Skype) when we weren’t laughing uproariously.

Bambi: Remember when Claes bit into a Chinese fortune cookie, made a face, and complained that there was paper in his cookie?

Gags or lines often in bad taste or politically incorrect, but biting and pure. No facade or pretense, just gutsy and honest observations with ever-present sardonic over-tones. Guards-down: the sort of rapport you can otherwise only have with a mate from school or the military, and hopefully with your marriage partner. (Or as they call them in Sweden “sambo.” Only forty percent of Swedish people marry—the rest live together under the label “sambo.” Never any spousal support after a break up, but child support works the same way, married or “sambo.”)

Claes had two lengthy “sambo” relations, each lasting about ten years. But he lived alone for the last fifteen years. He felt he lived full life, but regretted that he had not found a partner to share his later years with. He had a preference for exotic appearance and had relations in Latin America and the Middle East which never materialized into something that could become reality back in Sweden.

Bambi: Maybe he lived alone because of his famous stubbornness, huh? Would anyone else behave the way Claes did when airport security told him he couldn’t fly with his pocketknife? He wouldn’t give it up to the security officer, whom he knew would keep the gorgeous little knife. Instead, he was determined to destroy it. Except… it was a strong little knife, a fine German one, and he almost missed his flight because it took him so long!

His love was travel, photography, and the study of ancient civilizations (art, monuments, and history). He spent fifty years taking magnificent photos in every corner of the globe. He was a lecturer in Sweden with a strong following and his appearances always drew an adoring crowd of fans. It was not a big financial reward since culture lectures are not exactly big money-makers, but he was re-booked over and over for the same venues, year after year.

Bambi: Let’s not forget his love of tree-killing! Has any man felled more trees than Claes has? I was awed when I watched him single-handedly take down a huge mesquite in a tricky position at our Vegas house. But it was nothing compared to seeing him waving in the wind at the top of a giant fir on his country house property—a man with a fear of heights, yet! Over the years, I’ve watched his mountain of tree roots grow.

Oh, we did so much together. We gardened, we went on petroglyph-seeking road trips, we cooked. He taught me to make a killer Jansson’s frestelse. We made flädersaft together with the most old-fashioned tools.

All his friends will remember Claes for two things. His kindness and his desire to help. For many years he worked in human resources and it is amazing how many old friends have now come forward and expressed sorrow over Claes’s passing, always commenting on how much he helped them both professionally and with private trauma and complexities. He was a sensitive soul who wished well for others and always extended himself to others and their need for support.

When we were quite young, maybe about 12 years old, he wrote on a door to a tool shed that I had, “Claes is kind.”

I guess you could characterize Claes with those words—Claes is kind. I believe his friends will all remember Claes first and foremost as a kind and funny guy who passed away much too early.

Do you agree?