Is it legal to take photos at airport security checkpoints, or not?

Occasionally I’ll politely ask a TSA officer if I may take a picture. Usually, they say no. You know, “for security reasons.”

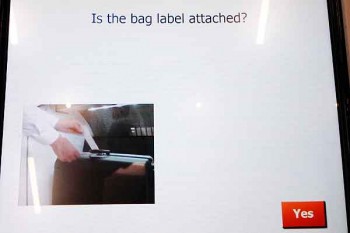

But not always. A few times they’ve said yes, but don’t take pictures of the X-ray machines. That always leaves me a little puzzled: which X-ray machines? Which part of them? But the TSOs didn’t seem to care and left me unsupervised.

Turns out that many police and security officers, TSA included, aren’t exactly aware of what’s allowed and what isn’t. Believing photography is prohibited, or erring on the “side of security,” or just exercising their authority, no photos is the default reaction.

And many of us, meek and obedient citizens that we are, we accept that. Or we choose not to challenge the uniform. We don’t know what’s legal and what isn’t, either. We tend to have, in the back of our minds, that it’s illegal to photograph bridges, airports, even police officers.

But yes, it is perfectly legal to take pictures at TSA checkpoints, with a few minor limitations (not the X-ray monitors, not if you interfere with the screening process). You can even videotape if you like—yes, you can film the officers, too. You might be challenged. You might be delayed by the officers. You might even miss your flight.

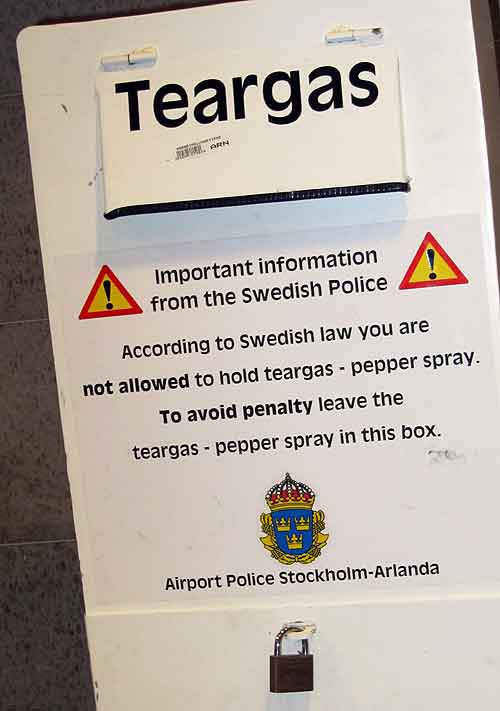

In fact, pretty much anything can be legally photographed from a public place (again, with a few exceptions), including crimes in progress, police officers, federal buildings, the New York subway, and security checkpoints. Yep, if you can see it, you can shoot it. Pretty much. I’m talking strictly about the U.S. here.

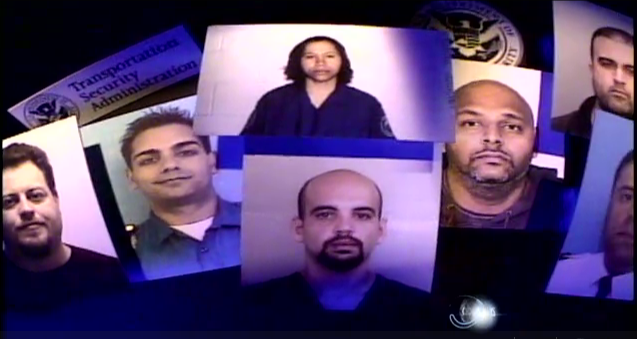

The Washington Post’s interesting July 26 article, Freedom of photography: Police, security often clamp down despite public right reports that photographers are challenging unwarranted restrictions and posting disallowed photos online (usually after being forced to delete them, then recovering them).

…rules don’t always filter down to police officers and security guards who continue to restrict photographers, often citing authority they don’t have. Almost nine years after the terrorist attacks, which ratcheted up security at government properties and transportation hubs, anyone photographing federal buildings, bridges, trains or airports runs the risk of being seen as a potential terrorist.

Portland Oregon attorney Bert P. Krages II has posted a useful, printable document, The Photographer’s Right: Your Rights and Remedies When Stopped or Confronted for Photography, which should be in every photographer’s camera bag. On his website, Mr. Krages says:

The right to take photographs in the United States is being challenged more than ever. People are being stopped, harassed, and even intimidated into handing over their personal property simply because they were taking photographs of subjects that made other people uncomfortable. Recent examples have included photographing industrial plants, bridges, buildings, trains, and bus stations. For the most part, attempts to restrict photography are based on misguided fears about the supposed dangers that unrestricted photography presents to society.

This issue is pertinent to Bob and me in our thiefhunting exploits. We often feel on thin ice when shooting thieves in the wild, especially abroad. And perhaps sometimes we are. We’ve been challenged and chastised many times. Once we had a videotape seized, but we’d seen it coming and swapped the tape for a blank, pocketing the valuable footage we’d just shot.

I was admonished, not too long ago, for taking a few shots of a pair of armed and uniformed police officers drinking whiskey at an airport bar. Okay, it was in Trieste, Italy, not in the U.S.; I have no idea what my legal rights were. The officers leisurely sauntered over, after they’d finished their drinks, and said no photos. Okay. Then they left. Much later, when I left, they made a beeline for me and made me delete the photos. Had they been lying in wait? Anyway, I couldn’t recover the images.