“You remember that famous movie, the one shot in Naples?” shouted Officer DC. “In this restaurant they filmed that movie. The whole world knows this section of Napoli.” He gunned his motorcycle and he, with Bob on the back, left me in the dust on the back of Officer M’s bike.

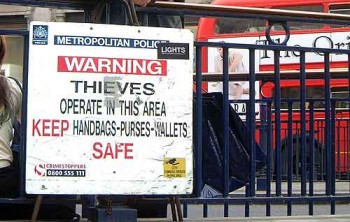

DC and M are Falchi—Falcons—two of Naples’ anti-theft plainclothes motorcycle warriors. The squad was launched in 1995 to fight, among other criminals, scippatori, the pickpockets and purse-snatchers who operate on motor scooters. Patrolling the city on souped-up motorcycles, the Falcons fight speed with speed, power with power, and strength with strength.

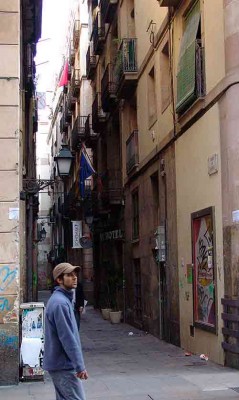

Our motorcycle excursion through Quartieri Spagnoli was not exactly a wind-in-the-hair power-ride, but it was bracing, a cop’s-eye view and guided tour of one huge crime scene. Hugging the backs of these brawny, spiky-haired, Levi-clad, cool dudes, we felt immune to danger—there, at ground level, but in a protective bubble.

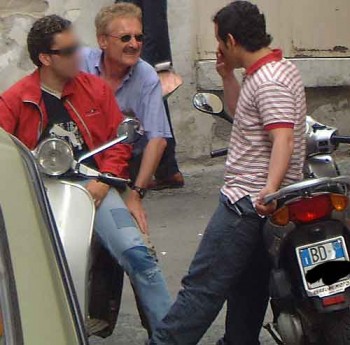

Bob and DC had stopped to talk with a guy on a Vespa as M and I caught up with them.

“This is AS, one of the best scippatori,” DC said. “He’s an expert with Rolexes.” The cop turned to AS: “These are two journalists from America. They want to interview you.”

“What are you doing here?”

“We’re making a touristic tour,” DC said with a sweeping gesture.

“How many Rolexes do you take?” Bob asked. He had a video camera in his hand but it was pointed at the ground.

“In a week? It depends. Where are they going to show this movie?”

“In America. In Las Vegas. Hey—this man is better than you at stealing!”

AS didn’t react. “Are you filming this? Are you filming me and everything?”

“How many watches do you take in a week?” Bob persisted.

“I take maybe ten Rolexes in one week. Hey, I don’t like this movie you’re making. You’re going to show a bad image of Napoli.”

“This guy makes films about crime in all different cities. Quartieri Spagnoli will be famous in America.”

“AS, how much do you get for one Rolex?”

“$16,000 [in US$]. For, you know, the one with diamonds all around.”

“Now we are friends with Bob. We can visit him in America!” Officer DC started his bike.

“Can I call you on the phone?” Bob asked. “Later, when I find someone to speak Italian for me?”

“No, I don’t want to give you my phone number.”

“Bob is okay, we’ve known him for many years.” Translation: give him your number.

“Okay, you can call me. Here’s my number.”

“Why is it different? Is it new?”

“Ah, I changed the SIM card.” Translation: I’m using a different stolen phone.

Bob and I had wanted a good look at Quartieri Spagnoli ever since our unexpected introduction to a trio of scippatori—from behind. We’d heard from other officers that the police don’t even go into this district except in squads of four or more. It was a war zone, they told us. Neapolitans disown Quartieri Spagnoli as other Italians disown Naples.

As we rode through the narrow lanes, DC told us about his symbiotic relationship with AS.

“AS has a lot of respect for me, that is why he gave you his number. He gives me information about the criminals here. We cooperate.”

AS is an informer—he rats on major drug activity. In exchange, the Falchi close their eyes to AS’s vocation. Unless, that is, a tourist comes complaining to the police about a Rolex theft. In those cases, Officer DC can have a chat with AS, and AS can do some digging, find out who did the swipe, and try to recover the item. Not that it always works….

DC stopped his bike to point out some of the quarter’s highlights.

“Look at all the laundry hanging from the balconies. Typical for this area. And here, this is one of the squares where the mob is very big, the Camorra. They all have their own areas and their own crimes—drugs, prostitution, stealing…”

“Do the grandmothers really sit in the upper windows watching for Rolexes?” I asked. It sounded like a myth, but I’d heard many times that theft here was a family affair.

Someone whistled—the piercing, two-finger type.

“That means police,” DC said. “They’re warning their friends that we’re here. Yes, the women sit on their balconies and when they see something to steal they call their sons or grandsons to come by on their scooters. It’s true.” He twisted around to look at Bob. “You must be careful with your video camera. These are gangs of thieves we’re passing and they’re looking at it. They can steal it.”

We paused in front of the funicular, the very one that inspired the classic Neapolitan song “Funiculi, Funicula.”

“Here in Piazza Montesanto there are many pickpockets, near the underground station. They steal many wallets in this area. And the funiculare is here. We have four video cameras watching this Piazza. There’s a lot of drug dealing here, too.”

Most tourists never venture into these areas of Naples’ old town and, but for the threat of theft, it’s a shame. Although we have no excuse to describe them in this book about criminals, most Napolitanos are warm and welcoming toward visitors; Bob and I adore their casual, urbane tradition. With its lively outdoor culture and its heart on its sleeve, Quartieri Spagnoli is the heart and soul of the place I call the city of hugs and thugs.

Excerpt from Travel Advisory: How to Avoid Thefts, Cons, and Street Scams

Chapter Five: Rip Offs: Introducing…The Opportunist

Also read How to Steal a Rolex

![]()