Prowling and preying with impunity, the pickpocket pair cared little about hiding their business. Yet none of the mighty swirling masses intent on going this way or that, paid them the least attention. Such is the state of street crime in St. Petersburg, Russia.

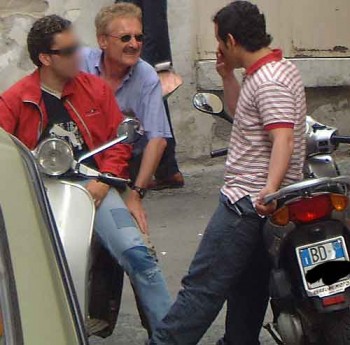

The thieves appeared aimless at first: bouncing around the intersection, crossing and recrossing the street, pausing to look into a window, only to turn and go back the way they’d just come. To anyone glancing at them, they blended into the crowd without suspicion.

Bob and I locked onto them the moment they appeared in front of us. (I’ll tell you why in the next post.) To watch the team’s activity for more than a minute is to understand their motive.

We happened to be in St. Petersburg, Russia, but it could have been anywhere. The location was perfect, and well-known to us from past thiefhunting exploits: on Nevsky Prospekt, the main drag, outside the area’s only Metro station. A very busy corner, human traffic ebbs and flows to the beat of the traffic lights and the comings and goings of underground trains.

A variety of police seem to patrol the area sporadically, strolling along in pairs, stopping briefly outside the Metro station doors. They have no apparent effect on the thieves we happened to be observing.

In years past, we’ve seen certain pickpockets operating day after day, month after month. Locals and expats come to recognize them, as of course the police do.

Street crime in St. Petersburg, Russia

Now locals tell us they see and hear of fewer thieves on the streets. Rather, the pickpockets prefer to work inside the Metro. Tour guides told us the thieves are more prevalent now inside the museums, in the Hermitage, and on the Navy ship Aurora; in other words, where the crowds are, where the tourists are.

Our observant friend who works at the art market on Nevsky Prospekt says the thieves stay on the move, never pausing. Indeed, that’s what we observed as we followed this brazen pair.

After they’d zigzagged around the area for about twenty minutes, halfheartedly hunting, I followed them down the street where they hopped onto a rather empty bus. If stealing aboard were their intent, they’d have waited for a crowded bus. In this case, they got on the bus simply to be transported away.

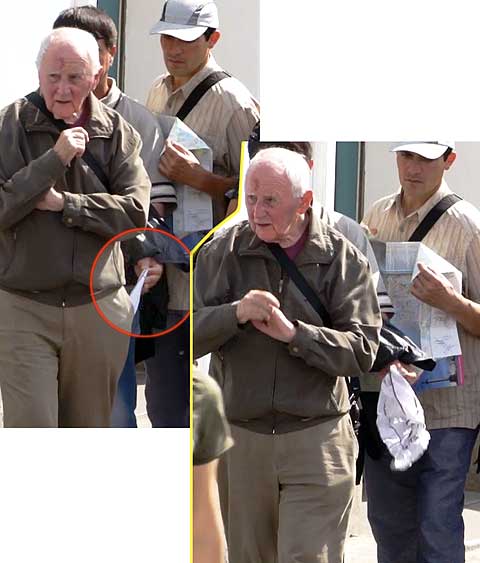

When they’d gone, I went back to my post outside the Canal Griboyedova Metro station. Sure enough, after ten minutes or so, the pair came sauntering back to the corner. This time they locked onto a mark, a stooped geezer whose shoulder bag dangled behind him.

The two trailed the old man as he meandered, staying behind him, one to the left, one to the right. The mark moved erratically and paused often: to look in a window, to cross the street, to gaze along the canal toward the magnificent Church on the Spilled Blood. Each time the thieves got close behind him, they’d get into theft position: one of them would unfold a map and use it to shield the view.

The problem was, they were a team of only two. They lacked the vital third member, the blocker. A blocker would have stopped short in front of the mark, forcing him to stand still for a moment—just long enough for the pickpocket to do his thing. A proper pickpocket crew of at least three individuals choreographs its moves like a Russian ballet.

Without a blocker, the pair couldn’t control their mark. They had to rely on natural reasons for him to pause. Alternatively, they could try to work in motion, which is much more difficult.

Finally, that’s exactly what they did. I was behind the thieves when they went for the pocket—not the hanging bag. Bob was some 20 yards in front of the threesome, but got a good shot with his new Sony NEX-VG10 video camera, thanks to its powerful long lens and stabilization.

In Bob’s footage, we see everything. The thieves’ great concentration, a hand in the pocket, the partner’s readiness. Then the extraction, the unfurling of the stolen handkerchief, the smooth passing of it to the partner. And through it all, the unsuspecting victim shuffles on.

The thieves weren’t fazed by their lousy haul. They stayed right on their prey, attempting another hit on the same pocket. They must have seen or felt the weight of something hefty inside (by “fanning“), and it was clear that their victim was oblivious to them. So was all of mankind, as far as they were concerned. They operated as if invisible to the world.

Or as if they’d paid for the privilege of haunting this stretch of Nevsky Prospekt for this time period. We’d been told more than once over the past 13 years that pickpockets pay police for permission to work at a specific time and place. We have not confirmed that this system is still in effect but… old ways change slowly, if you know what I mean.

On previous thiefhunting expeditions in Russia, we’ve used hidden cameras, or at least unnoticeable ones. This time, Bob’s bulky Sony, held up to his eye and aimed directly at our quarry, made his interest obvious. One of the pair noticed and, when he crossed in front of Bob, hid his face with his jacket. Then he peeked: still filming?

The victim eventually wandered off and stood on the canal bridge until the pickpockets gave up on him. Still unaware of his followers, he trudged back down the block to the bus stop and sat on the bench. Perhaps he was aware of something amiss, because he began an inventory of his belongings, starting with his wallet, taken from the same pocket the handkerchief had been stolen from. Did he notice the handkerchief was gone? Was there something else stolen that we didn’t catch?

More on pickpockets in Russia:

Russian Rip-off: pickpockets and thugs