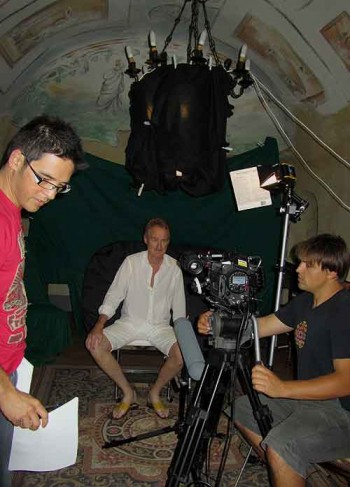

On making a documentary. As I said, you’d think a documentary is just a camera following the action—but the action must be lit and wired for sound. And the cameras have to catch it from all the right angles.

It takes a long time to set up each scene, even if we’re just talking to the camera in our hotel room. Our team is shooting on a Red, the ultimate digital cinematography camera, the most expensive, the hardest to use. It records raw data without compression and therefore requires enormous hard drives. The Red is top on the list of our investor/distributor’s camera requirements; and our investor/distributor is a name in documentary films known and respected by all (even you). Their requirements are stringent.

Our days are long, starting very early and ending past midnight. But whatever time we get up, director of photography Van Royko has been up hours earlier, preparing the Red One. Director Kun Chang stays up hours later, transferring the day’s data. We’re all working non-stop, even on our scheduled day off. The payoff will be a phenomenal documentary film.

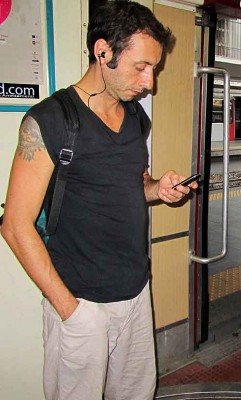

I quickly get used to the sound man tucking the tiny microphone between my breasts, running wires around my body, and cramming the battery-pack transmitter and excess cable down my pants. Repeating simple actions becomes routine: “can you get back in the car and get out again?” I learn to ignore the giant lens two inches from my face while I brush my teeth or change earrings. These small acts, while unimportant, will eventually help tie together the big events in our story. In the end, only a few seconds will be used—just a flash, a tiny fraction of the footage the filmmakers shoot.

At the beginning of the shoot, I’m determined to be conscious of my posture and to remember to smile. That works for about half a day. When you’re eating and packing and arguing in front of the cameras, you give up vanity and just be who you are. In fact, I’m later surprised to discover that I loathe the prospect of projecting myself unrealistically, which results in a scene in which I remove my shirt on camera because that is what I would have done had the camera not been there.

On the other hand, I want to be somewhat careful of what I say. Sound bites can be taken out of context. I can’t unsay something. So maybe I’m not totally myself after all.

I don’t keep track of what I’ve worn. Often, it’s ugly, neutral “thiefhunting” clothes, chosen to be forgotten, unnoticed by those we follow. Events happen fast and unpredictably, moving from location to location. Sometimes the filmmakers need “pickup shots:” closeups or establishing shots that help explain to the viewers where we are or how we got there. “Can you put on the clothes you wore three days ago?” Hmmm, what was that?

I guess I can divide the shooting into three categories.

-

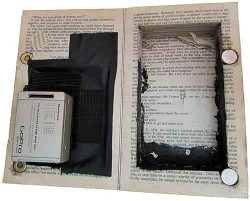

- 1. Bob and my thiefhunting activities. That would include hidden camera rigging, searching for thieves, and interacting with them.

-

- 2. Interviews. Bob and me, separately or together, looking into the camera and talking.

- 3. Fly-on-the-wall. Bob and me going about our business with cameras watching. At breakfast, in restaurants, in our hotel room, and in the city.

The second two categories are easy and standard for documentaries. The first is extremely difficult, since we don’t know what we will do, what we will find, or what might happen. Yet, the crew must follow us, must remain invisible, and must be ready to turn on a dime. They must compromise sound and image quality in order to use equipment that keeps them maneuverable.

We have a “fixer” whom I’ll call Rosie. A native of this city, she is a well-connected miracle-worker. She zips around town on her motorcycle in the aggressive local driving style, and claims the iPad changed her life. From it, she can do anything, anywhere.

Some days into the shoot, Bob surprises everyone by getting a haircut. The producer notices instantly and her head falls into her hands. Bad boy, Bob. Director Kun Chang explains that the haircut screws with his timeline, making it impossible to intercut scenes, especially interviews and those pickup shots. By sheer coincidence, sound recordist Michele also gets a haircut on the same evening off. This shouldn’t matter for a sound man, but Michele is an integral part of the film as on-camera translator, so it matters a lot.

There’s much more exciting stuff to tell about our interactions with thieves, but I’m having trouble keeping up with daily posts. The story continues!