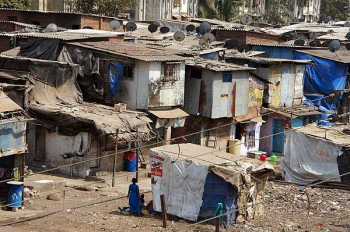

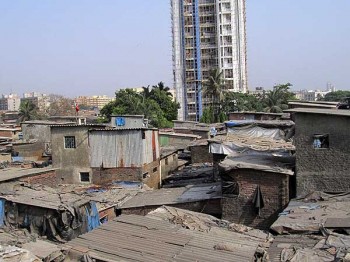

All these Mumbai stories of trains, crowds, swamis, the slum called Dharavi, and promises of more stories… What you’re really wondering is: did the Thiefhunters find any pickpockets in Mumbai?

The Thiefhunters did, and lets not even count the two boys found handcuffed together at Kurla train station, roped to an undercover policeman. We rode the train with them where they had to sit on the floor, like dogs on a leash.

Bob and I spent days on trains so crowded we couldn’t move, and joined pushing-shoving boarding mobs that were a pickpocket heaven. With opportunities like those, we thought we’d find plenty of thieves.

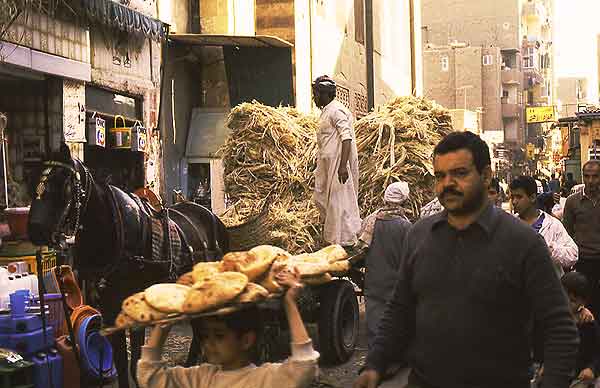

We road buses all over the city, which turned out to be a fascinating way to see Mumbai off the tourist track. At stops along the way, we hopped off and onto buses that barely paused for passengers. Where large groups waited to board, the rush was sudden and desperate—perfect for pickpockets. They should be able to do their work without boarding at all, putting instant miles between themselves and their victims. At a bus stop on the edge of a large slum, we spotted a pair that did board. The ticket-taker noticed them too, and pushed them off at the next stop.

Interestingly, every bus we rode carried a human ticket man who checked and sold tickets. Whereas on trains, we saw no controls whatsoever.

At end-of-the-line bus stations, huge orderly crowds lined up in a metal cattle mill for each route. Buses came at short intervals, again barely stopping. Passengers surged on while a uniformed people-manager tried to keep order. These men too watched for pickpockets, and told us that most thieves stalked bus passengers on the two monthly paydays. Those are only the pickpockets who get caught, I say.

From the excellent, new, non-fiction book I just read, Behind the Beautiful Forevers, I gather that beating is a common enterprise in Mumbai. Among the book’s stressed-out, almost-zero-income community members, everyone partakes: parents beat children, brothers beat sisters, and kids beat each other up regularly. In the book, police are notoriously brutal. When we interviewed Mumbai pickpocket Rahul some years ago, he’d been beaten to a pulp by train passengers who’d caught him in the act. This, we are told over and over, is the way it works in Mumbai. A deterrent, possibly.

And when our friend Paul McFarland was mugged for his wallet, the wallet, his ID, and credit cards were all returned some 15 minutes later, with only the cash missing. Why? Karma.

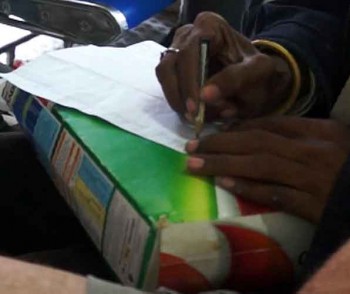

The pickpocket we spoke with this visit was from Andhra Pradesh, an Indian state southeast of Maharashtra (where Mumbai is). He specializes in highway robberies, getting a driver to pull over whereupon he steals their stuff. But the smooth pickpocket moves he showed us betrayed his real job skills.

We promised not to photograph his face, but I will say this: although he was of average height, weight, and appearance, he was the type who would stand out in a crowd as suspicious. Perhaps it was his demeanor.

Our translator spoke English and Marathi. Our barefoot pickpocket spoke something else, so our conversation was rough. The routine problem and frustration with impromptu interviews with thieves—not everyone is willing to get involved with criminals.

The thief described himself as a married Muslim with a wife and five children living in the next-door state. In the time-honored tradition, he learned pickpocketing from his father. When he demonstrated his technique, he couldn’t help using a specific move with his leg, in which he raised it to press his knee into the back of his victim’s leg. One indicator common to career pickpockets that we notice over and over is that their particular style is engrained and they can’t change it, even for a demonstration. His fluid motions and the confidence with which he showed them telegraphed that he was very practiced. We couldn’t figure out whether he currently practices both pickpocketing and highway robbery, or if he’d shifted from one to the other.

Bob and I have spent a lot of time thiefhunting in Mumbai, and our conclusion remains: although pickpocketing is not unheard of, a visitor is not very likely to be a victim. That doesn’t mean one shouldn’t practice safe-stowing and down-dressing—but I assume that readers of this blog already know that.

Also read: Street Crime in Mumbai

Knock-out Gas on Overnight Trains

Technicolor Mumbai