NAPLES, ITALY, the week before christmas. Everywhere we go, people recognize Bob from the film. They stop in cars in the street (1:30 a.m. last night it was the only way we managed to cross the busy street), pop out of shops, ask for photos, approach us in restaurants. We’re amazed!

This afternoon we’re to meet Michele, who was sound man on our film and, more importantly, translator extraordinaire. He’s from Naples but now lives in London, and he’s flown in to spend three days with us before christmas with his family. He’s also arranged a meeting for us with two filmmakers, one of whom wrote the screenplay for a renown crime film.

Still no luggage and I can’t continue to walk long distances fast in these heels. I buy some flat boots for the sake of speed and endurance on the rough stone streets. Later, I also succumb to a pair of frivolous shoes. Italy—what can I say.

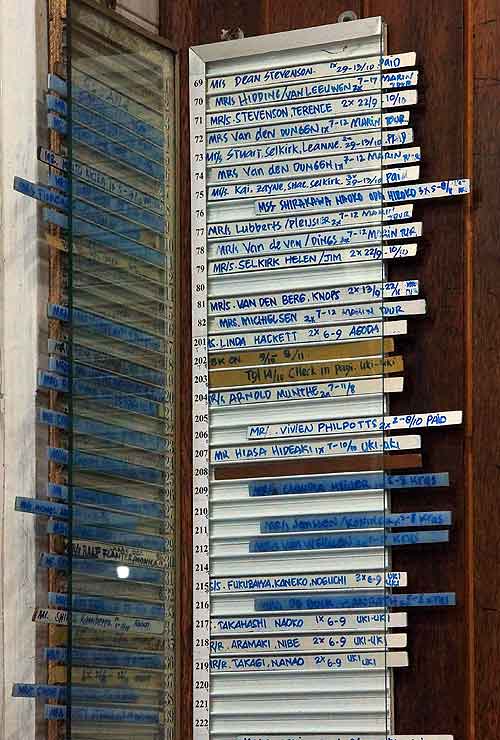

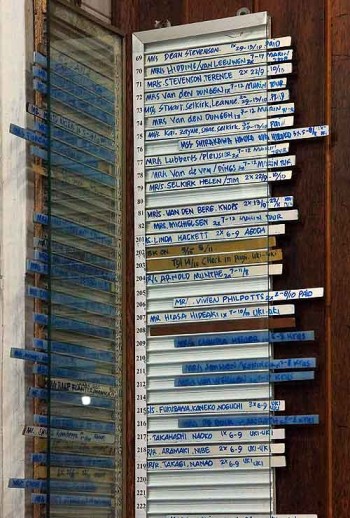

We grab a late lunch before our 5:00 meeting with Michele. We haven’t seen him since the film shoot in September ’10, more than two years ago—but it’s like yesterday. He is sweet, smart, and always good company. As to working with a criminal element, he’s the best. The thieves like him. They trust him. I think he softens Bob’s prickliness, too. We catch up in the hotel lobby for a while before leaving for our appointment with Franco.

Michele has a car (parked miles away—thank goodness for the boots!) and drives us to Franco’s, where we’re to have dinner with his family. Franco was the main pickpocket in our NatGeo film, the thief we’ve been exchanging long emails with for two years. We went to his house for dinner a year and a half ago (with another translator).

Michele drives us in his family’s old rickety car. Even so, he’s concerned about leaving the unattractive car on Franco’s street, such is the neighborhood. Franco opens the heavy gate to his apartment complex and locks it behind us. I imagine all his neighbors feeling safe inside—locked in with a thief.

Franco had asked us not to talk business in front of his young children because they don’t know his job. He said we’d go out after dinner to talk thievery stuff. First, he shows off the apartment, which had undergone major remodeling since our last visit, much of which was done by Franco himself.

The apartment is almost unrecognizable. A long stone bar now divides the kitchen. (They call it the “American bar”—why? paid for from an American wallet?) There’s new built-in cabinetry, a wall closed where there had been a door, the door moved to the other side of the room, a closet turned into a passage, etc. It’s all beautifully done. The boys’ room is full of slick built-in furniture, bunk beds, desk, flat screen tv, computer, etc. It’s spotless, and the tan color-palette is calm and mature.

The living room flat screen tv is gigantic. They leave it on during our entire visit, even though the dining table is right in front of it. A wifi router blinks on a shelf. Franco builds large, complicated model ships. Two are on display in glass cases in the living room. I remember one of them being half-built last visit. Franco is good with his hands in more ways than one.

Bob and I are both dying to take photos but, out of politeness, we refrain. The family lives very well. They aspire to an upscale life. Franco must work hard to acquire such luxuries. Or maybe he just works the credit cards.

Eight Margherita pizzas are delivered for dinner. No silverware is offered. Bob and I follow suit when each member of the family folds the lid of his individual pizza box underneath. Michele can barely take a bite since he’s translating everything that’s said by everyone. After dinner, Franco brings out a giant album in a gorgeous leather box which documents his childrens’ recent first communion. The album is beautifully printed, like the ultimate Apple book. After we slowly go through it and admire every photo, he brings out another album-in-a-box. This one is his and his wife’s recent 25th anniversary church ceremony and party.

They’re a stable, upwardly-mobile, almost-ordinary middle-class family. All good-looking and likeable. It’s only Franco’s job that’s objectionable; but is it any worse than a cigarette company executive’s? There are many repugnant jobs, many of which must be held by likeable people. I can like Franco, but not his job. That’s proven.

Bob, Michele, and Franco disappear into a bedroom to talk. The wife has slipped away. I’m left with the children, who struggle to ask me questions using sign language, their limited English, and Italian, of which I speak none. Hopeless. Eventually I grab Bob’s MacBook Air, fire up Google Translate, and we suddenly have all the conversation we want. It’s excellent—though eerily silent.

It’s past midnight by the time we leave the house with Franco. We stand out in the street talking for another 45 minutes, scooters continuously buzzing close by. Michele only tells us later, on the way home, how nervous he was standing there, especially knowing Bob was loaded with computers and cameras hanging from his neck. On a deterrent-scale, neighborhood-resident Franco might not outweigh juicy-target Bob. Still, nothing happened.

Because traffic is crazy in Naples, even after 1 a.m., Michele drops us off in town about a mile from our hotel—against his better judgment, but on our insistence. Driving us to our hotel through choked streets would add another hour to his trip home. I’m nervous, of course, but Bob isn’t. We stand waiting to cross the wild traffic when a car stops and the men inside roll down the window and yell “Bob Arno, you are great!”

This is Part 2. Read Part 3.

Read Part 1.